In their 1998 paper, Stall & Stoecker identified two main types of community organizing styles: the Alinsky style, based on the principles of 1930s organizer Saul Alinsky, and women-centered (or coalition building), which is derived from the organizing practices of women and people of color. As Stall & Stoecker describe it it, “the Alinsky model begins with ‘community organizing’–the public sphere battles between the haves and the have-nots. The women-centered model begins with ‘organizing community’–building expanded private sphere relationships and empowering individuals through those relationships”[1] Working at the same time as Alinsky, Clara Shavelson mixed both of these methods in her career, organizing women in her neighborhoods to a fair amount of success.

In the Alinsky model, the organizer is not a community member but an outsider who places organizing above all else, including family. This model emphasizes actions, often conflict, in the public sphere between the community and the elites/government. The women-centered model has a collectivist emphasis, and is less focused on public sphere action and supportive of looser, local actions that may not garner the same kind of attention as Alinsky style actions.[2]

In keeping with the collectivist nature of women-centered organizing, there is space for Alinsky style public sphere actions. However Alinsky’s fairly narrow principles for community organizing offers little or no room for the kind of organizing that emphasizes an ethic of care and intellectual empowerment of individuals.

The immediate issues the housewives of Brownsville faced in the early 1910s,were rent increases, evictions, and food cost increases. Shavelson gained renown in Brownsville for her street corner soapbox speeches against greedy landlords, and led her entire building in a rent strike. Other women were also engaged in public actions, , with several of them featuring the typical masculine tactic of violence. In February 1917, after learning of price increases at a local market, a group of women in Brownsville started what the press described as a “food riot”[3] The situation quickly escalated and resulted in a police officer accosted by angry women, and four women were subsequently arrested. The article describes the officer’s uniform looking as “if it had been through a threshing machine” and the women as “infuriated” and “hysterical”[4] At the police station an even larger group turned out in support of the four women, who were ultimately released. It is unclear if this was a planned action or a spontaneous one, but the ability to mobilize people to the courthouse

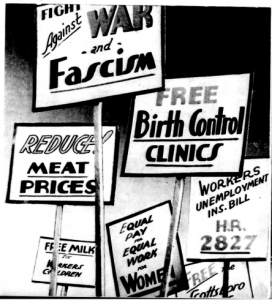

After moving to Brighton Beach in 1924, Shavelson expanded her organizing efforts. She helped to create groups like the United Council of Workingclass Housewives (UCWH), The United Council of Working Class Women (UCWW), and the Emma Lazarus Tenant’s Council to provide a collective base for women to meet, talk, learn, and plan for action. These groups provided a place for supporting and making visible women’s activism. While Alinsky-style organizing typically focuses on a single issue and is interested primarily in upsetting the power dynamic, Shavelson was well aware that the women in her neighborhood were concerned with multiple intersecting issues, and that education and conversation were a powerful tool in addressing these issues.

Throughout her life, she continued to be involved with local actions against markets, butchers, and landlords, but she also participated in Alinsky-style actions that confronted the larger power structure. In May 1935, during a city-wide meat boycott, Shavelson and three other women met with the New York City Commissioner of Markets, and when this proved unsatisfactory, they demanded a meeting with Mayor LaGuardia. The newspaper account clearly sets the women, just trying to feed their families, against the heartless government and meat industry. This is the type of action that Alinsky, who wrote that organizers should garner sympathy by baiting the establishment would approve of.[5] The culmination of this boycott was in June 1935, when there was a “coordinated protest against the large corporations controlling meat prices in the United States”[6]

The actions and successes on a local scale empowered the groups involved to try similar tactics on a national scale. In 1935, the UCWW demanded a congressional investigation into food prices and a reduction in the price of meat. They met with the United States Secretary of Agriculture to ensure their demands were heard.

Although there were plenty of failures in both organizing and in gaining institutional power, the mixed methods worked well for Shavelson. Reading and discussion groups created spaces for women to engage with ideas and theories. Even though the UCWW didn’t survive the McCarthy era, within a few years of its 1931 founding there were 48 chapters in New York City alone, a certain sign of success. If even a small percent of the women involved in a UCWW chapter remained politically active then at least one of the goals of the group was realized. The attention grabbing public sphere actions made city and federal officials take notice and implement change. The New York Times reports that as a result of citizen pressure on the federal government, including the UCWW meeting with the Secretary of Agriculture, the Labor Department allotted funds to complete an investigation into price fixing in the meat industry.[7]

Shavelson didn’t write explicitly about her organizing strategies. She was guided by an understanding of people based on her experience with the labor and suffrage movements, along with her own perspective about the intersectional nature of gender and class oppression, and her interest in education. Combined, these experiences and understanding of institutional power guided her in creating effective organizing strategies that both expanded the understanding of those who were involved and also attempted to shift the balance of institutional power.

—

[1] Stall, Susan, and Randy Stoecker, “Community Organizing or Organizing Community?: Gender and the Crafts of Empowerment,” Gender & Society 12, no. 6 (1998): 733.

[2] Ibid., 757.

[3] “Policeman Mauled by Rioting Women; Four Under Arrest,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, Feb. 21, 1917.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Alinsky, Saul David, Rules for Radicals; A Practical Primer for Realistic Radicals (New York: Vintage Books, 1972), 100.

[6] Orleck, Common Sense & a Little Fire, 236.

[7] “Housewives Demand a Food Price Inquiry,” New York Times, June 21, 1935.