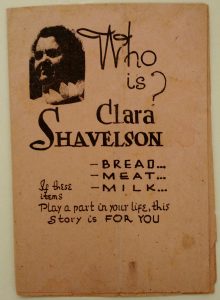

Clara Lemlich Shavelson is known primarily for her part in the 1909 garment workers strike in New York City, often referred to as the Uprising of 20,000. At the time, immigrants dominated New York City garment industry jobs, with many of the low-skilled positions going to immigrant women. Employees worked long hours, often in dangerous conditions for low wages with no protections. In these working conditions, collective action through the union labor movement proved crucial to the well-being of workers in the garment trade.

That Shavelson understood the need for collective action to provide protections is no surprise. As a child in a Jewish household in the Russian Empire, she encountered injustices early on, and with her own family. In her traditional, Yiddish-speaking Jewish household, her father was a scholar while her mother ran a small shop to support the family. Her brothers were educated in Russian and Hebrew, while Shavelson was forbidden from learning Russian and discouraged from furthering her education. Shavelson was a determined child, and the stories from her childhood point to a strong will and a desire to learn. They also have the feel of legend: learning to read Russian in secret from neighborhood children, taking in sewing to pay for books which her father then found and burned, being passed revolutionary anti-Tsarist tracts by a sympathetic neighbor, which instilled in her that “only revolutionary thinking could truly free the mind.”[1]

The 1903 Kishinev pogroms were a turning point for the Lemlich family; they decided it was no longer safe to stay, and by 1904 the entire family was in New York City. Shortly after her arrival, Shavelson, who had some sewing skills from her native Ukraine, found work in a garment factory. She officially joined the International Ladies’ Garment Worker Union (ILGWU) in 1906 and was a member of her local executive board. With her emphasis on “revolutionary thinking” and willingness both to speak her mind and put her physical safety on the line, Shavelson became well known in the garment trades as an agitator and organizer for workers’ rights, and was instrumental in strikes in several factories between 1906 and 1909. She led worker strikes at both the Weissen & Goldstein Factory and the Leiserson Factory, and was a regular speaker on picket lines around Manhattan.

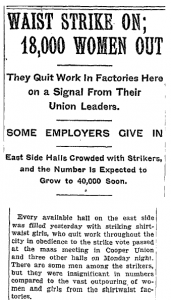

Her star turn came in November 1909. Taking the stage at a union meeting at Cooper Union, following several union leaders, including American Federation of Labor president Samuel Gompers and Women’s Trade Union League President Mary Dreier, Lemlich demanded action–a strike. Recalling the strike years later, Lemlich noted that she was compelled to speak: “[I] had fire in my mouth,” she explained.[2]

Her star turn came in November 1909. Taking the stage at a union meeting at Cooper Union, following several union leaders, including American Federation of Labor president Samuel Gompers and Women’s Trade Union League President Mary Dreier, Lemlich demanded action–a strike. Recalling the strike years later, Lemlich noted that she was compelled to speak: “[I] had fire in my mouth,” she explained.[2]

This moment captured the public imagination, and has been reproduced in film, stage, and fiction. Although often portrayed as an ordinary worker who gathered enough courage to speak her mind, Shavelson was in fact a veteran of union organizing and strikes, and her speech was no surprise to those who knew or worked with her.

The Uprising of 20,000 lasted 14 weeks, and the experience of supporting over 20,000 striking workers so exhausted Shavelson that she was forced to go to the country to recover her health.

This is the point where most accounts of Shavelson leave off. She is often mentioned in passing with relation to the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire in 1911, a factory where she was not employed. But for the most part, the public story of Clara Lemlich Shavelson ends when the strike does.

Of course, the end of the strike was neither the end of her life, nor of her activism. After the strike, Shavelson found work as an organizer for the Wage Earners Suffrage League. In 1912, she married, moved to Brooklyn, and started a family, leaving garment work, and exchanging union organizing for a different kind. In Brooklyn, she organized women in her neighborhood–wives and mothers–to engage in consumer activism such as food boycotts and rent strikes. For Shavelson, the personal was political, and she was well aware of the effects that collective action, could have, whether from a group of workers or of housewives. She believed that sweeping social change was necessary and possible. For Shavelson, fighting for what you believe in was the best way to live one’s life.

After leaving garment work, Shavelson maintained ties with the labor movement, even after she became disillusioned with the union leaders, whom she felt to be too conservative and too focused on short term gains. Shavelson joined the Communist Party, where she found others who were committed to revolutionary thinking in the same way she was. In a conversation with her daughter Martha, Shavelson said of her move away from organized labor that “the great majority of workers merely believe you have to get a little more pay. A Communist wants more than that. You joined for a higher life.”[3]

After leaving garment work, Shavelson maintained ties with the labor movement, even after she became disillusioned with the union leaders, whom she felt to be too conservative and too focused on short term gains. Shavelson joined the Communist Party, where she found others who were committed to revolutionary thinking in the same way she was. In a conversation with her daughter Martha, Shavelson said of her move away from organized labor that “the great majority of workers merely believe you have to get a little more pay. A Communist wants more than that. You joined for a higher life.”[3]

Mindful of her early days without access to education, Shavelson organized reading and discussion groups for housewives in her neighborhood. She ran for New York City and State office, and campaigned for other candidates whose vision she believed in. She raised money for unions out on strike, and led delegations of people to City Hall and to Washington, D.C. in support of lower food prices, federal unemployment, and world peace. Along with her husband Joe, she raised her children in an activist household.

Shavelson ended a 1965 letter recounting her involvement in the 1909 strike by saying that “insofar as I am concerned, I am still at it.”[4]

In fact, she continued to be at it until her death in 1982. At her retirement home in California, Shavelson convinced the administration to support the United Farm Workers produce boycott, and helped the nurses organize for union representation.

One of many women who committed her life to revolutionary action and the advancement of women and workers in New York City in the 20th century, Shavelson’s name and her work aren’t as well known today as others.

With this history in mind, this project seeks to make visible the entirety of Shavelson’s activism beyond the 1909 strike. Not a biography, this project is a documentary history that explores the traces left by a woman who lived a relatively public life and today is little known. This project aims to be an educational and exploratory tool, as well as a public resource that considers the intersections of organizing, power, and effecting change in New York City.

—

[1] Orleck, Annelise, Common Sense & a Little Fire: Women and Working-Class Politics in the United States, 1900-1965 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1995), 22.

[2] Von Drehle, Dave, Triangle: The Fire that Changed America (New York: Atlantic Monthly Press, 2003), 9.

[3] Orleck, Common Sense & a Little Fire, 223.

[4] Shavelson, Clara Lemlich, “Remembering the Waistmakers General Strike, 1909,” in A Documentary History of the Jews in the United States, 1654-1875, ed. Morris U. Schappes (New York: Schocken Books, 1971).